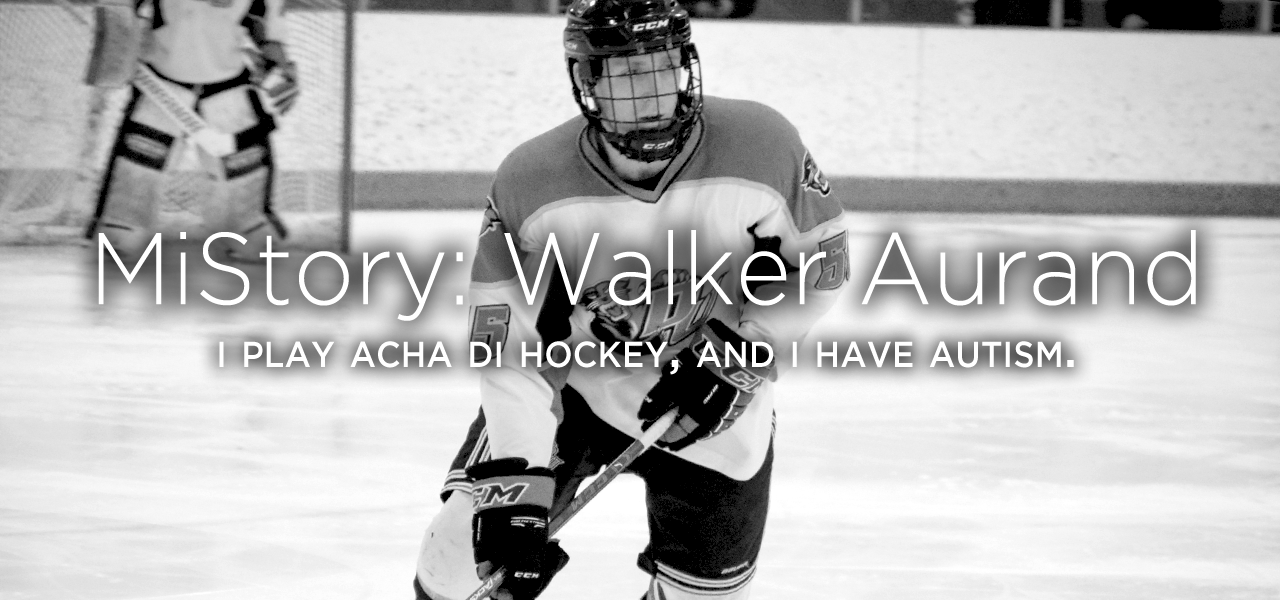

MiStory: I play ACHA D1 hockey, and I have autism (by Walker Aurand)

In MiHockey’s new MiStory feature, we let hockey people tell their own stories with their own words. Kentwood native Walker Aurand shares his own hockey story – a testament to overcoming adversity while playing the sport he loves. (Photos courtesy of Alexis Hoffman/AlexisJoyPhotography)

Do you have a unique hockey story you want to tell? Contact us at mh@mihockeynow.com.

I have read the articles written by young men and women like me often in MiHockey. I commend all their efforts and am in awe of their ability to write about themselves and their lives, and hockey experiences with such grace. Their experiences are so personal, their lives dotted with adversity and, as I have found out, seeking their dreams, so “painful” to write about. I am filled with anxiety and emotion that this publication wanted to help me publish my story of hockey, as it relates to my life. But, I also feel excited and compelled to write and share my story. I am doing this all for the love of hockey. It has been, at the very least, one of the saving graces of my days for most of my life.

I play ACHA Division 1 hockey at Davenport University in Grand Rapids, and I have autism.

Autism is a social and communication disorder that now affects one in every 68 children, and boys are five times more likely to have autism than girls. Today, there is no medical cure for autism. It is said that autism costs a family $60,000 per year on average for therapy and accommodations in school (per Autism Speaks). Autism is a spectrum disorder, which means that it can affect people on different levels. It can occur with many different levels of intellectual ability, as well. I have a milder form of autism called Pervasive Development Disorder, or PDD. I received this diagnosis when I was 2 years old, and my parents told me when I was 8. I did not fully understand what it meant until I was 16. One of the aspects of this is that my mind sees things as a series of movie clips. I remember conversations and things that I see exactly as they occur. That is very helpful academically, but it does not help me feel emotions.

Unlike most kids, I started school and therapy when I was 27 months old. I worked daily with occupational therapists who helped me learn how to use my body, eyes and hands together. Vision therapists taught me how to use my eyes to read. Speech therapists helped me understand how to use words to talk and understand words related to school. I also went to a weekly ‘play group’ with my mom where other high-energy kids like me learned to integrate our bodies with our brains so we could learn to speak more fluidly. I had difficulty learning to relate sounds to letters in order to read words.

My parents learned to use my athleticism at a young age to help me learn and spell. They did things like tie paper plates with letters on them to a hockey net and have me shoot pucks at them to spell out words. By the end of the second grade, I had become a very good speller – I went through hundreds of hours of therapies, which was very time-consuming for my family.

My dad started taking me to the rink to skate about this same time. At first he carried me in a pack that he wore, and eventually put me in skates to try for myself. I took to the ice quickly, and instantly fell in love with hockey. When my parents saw how much I benefited from moving on the ice, they decided that playing hockey would benefit me as much, if not more, that the other therapies I had been receiving. Whenever I took the ice, all my fears and insecurities left my mind. Hockey also gave me a strong sense of self at a young age, and taught me how to socialize with my peers. It wasn’t always easy, because I did not always get the humor that the guys used as they got older; I did not intuitively understand it. My parents had to explain a lot of it to me, which was very helpful.

As I moved into high school, I began to worry how receptive my teammates would be to me if they found out about my learning differences. Sarcasm is something that you deal with every day in high school, especially in a room full of hockey players. During my first year playing varsity hockey for East Kentwood, if one of the guys on the team made a joke to me I would have no idea if they were being serious or not. This made it difficult for me to be a part of the dynamic in the room sometimes. It wasn’t until my senior year that I started to pick up on and understand this better. My younger brother was on the team with me by then, and was my guide for understanding social cues. If it wasn’t for his help with this I wouldn’t have been able to pick up on sarcasm the way I do now.

I was both excited and nervous for what laid ahead of me after high school. After considering several teams, I decided that I would play that next season for the Dells Ducks of the Minnesota Junior Hockey League. The Dells is a popular summer vacation destination in Wisconsin, and while it attracts many visitors during this time, the year-round population is only slightly larger than my high school. I wouldn’t say it was culture shock, but it wasn’t the same as home. Nonetheless, I packed up my things and moved six hours away to Wisconsin for the next eight months to play and live with people I never met before. I was fortunate, however, to be able to play and live with one of my best friends from high school, Sherman Mowery, which made the transition easier for both of us.

Before I left, my parents talked to my coach and billet family to let them know that I had autism, and explain what it was. I never expected any special treatment because of my autism, but we felt it was important for them both to know this about me. My parents worked with me the summer before to teach me how to advocate for myself and establish a routine. This is another aspect of autism – the need for structure to manage daily activities. I was going to be responsible for getting myself ready to travel to road games, do my own laundry, and other things that my parents had done for me up to this point. Another area of adjustment for me was eating a wider variety of foods than I was used to. My billet family, the Barneys, introduced me to new meals, which were very tasty.

My coach in the Dells, Bill Zaniboni, was demanding, but also a great mentor who wanted the best for his players. His door was always open to us, and over the course of the season I became more comfortable talking with him about things that were on my mind, as well as what he thought was the best path for me to follow after junior hockey. He understood the difficulties that first year junior players face as they adapted to a new environment, and truly worked to understand how best to communicate with me. He is definitely one of the best coaches I have ever had.

Even so, I had some struggles with his communication style early on. He told us that if he yelled at us on the bench not to take it personally, but I still had a hard time with that. My parents encouraged me to talk with him about this and explain that I wasn’t sure if he was really mad at me or not. We had a good conversation about it, and he appreciated knowing how to communicate more effectively. I have learned that this is one of the traits of a good coach, and I will always appreciate this about Coach Bill.

A lot of people would say that junior hockey is business, which it is. But, the thing that I loved about the Dells is that our coaching staff and ownership were exceptions to this rule. They treated everyone like family and made you feel important. We had a really good team and ended up finishing first place in our league, capping it off by winning our playoff championship and qualifying for the Tier 3 national championship. Looking back, it’s no surprise we won, we had a team that truly cared for one another. I can still hear Coach Bill in my head telling us, “Do it for the guy next to you.” That’s what made us successful – you knew that guy next to you was going to be there to pick you up if you were struggling.

Even though it was a very successful year, I did have my struggles and had to learn to manage them myself. Sundays were often lonely after a weekend of games. I usually called my parents in the evening, and I remember feeling homesick when I talked to them. If I was having a problem, they would encourage me to talk to my coach or billet family about it, and walk me through the process of what words I needed to use to communicate effectively. Things like asking my billet mom to sew a button on my suit, ordering new sticks when I needed them and keeping my trainer informed about my recovery from a concussion I suffered near the end of the season – this was not always easy for me, but I became better at it by the end of the season.

While I enjoyed my time with the Ducks, a part of me really missed home and seeing all my friends. It was nice not having to worry about school during the week, but when I would see someone I knew from back home really enjoying their college experience, a part of me felt like I was missing out on something. Don’t get me wrong, playing that year for the Ducks was probably one of the best experiences with hockey I’ve ever had. I’m thankful for all the ups and downs that playing for the Dells that year taught me to handle. But there were times were I was just plain homesick. I missed seeing my parents in the stands and talking to them after the game. I also missed my brother and seeing him play, as well. One thing I learned about myself in juniors was that I needed to go to college closer to home so my family could see me play more often. I also knew that I would need the support from them to balance hockey with academics. During my exit interview with Coach Zaniboni, I expressed my interest in playing ACHA D1 hockey, as there were several good programs in Michigan. Davenport University was at the top of that list. If I chose to go play out of state somewhere, it would have meant moving even farther from home, and I didn’t want that. After considering a return to juniors for a second season, I felt like it was time for me to make a change. That’s where Davenport came in.

This probably will sound lame, but I really enjoy school. I have always had extra motivation to do well in school – my parents were told I was not supposed to read past a fourth-grade level when I was first diagnosed. As I progressed through high school, I required fewer classroom supports every year and wound up graduating with honors. I felt ready to start college, and begin working towards my goal of becoming a broadcast journalist when my playing days were over. That summer when I came home I was given the opportunity to play for Davenport University and Coach Phil Sweeney. I knew Davenport very well. My father was actually their first goalie coach when the program began, and I went to a lot of those games when I was younger. I remember that the team was good even in those early years, and crying whenever they lost (which was not often)! So, naturally, it was a fit for me from both a hockey and academic standpoint.

Despite having the luxury of being able to live at home for my first year of college, I was still somewhat nervous. I knew going into the year that I would probably be one of the youngest guys on the team (which I was) and it was slightly nerve-racking, because I wondered how group of guys who were all grown men between 21 and 24 years old would respond to having an 18-year-kid on the team. I just hoped I could make a good first impression on all of them. By the end of the year I couldn’t have asked to be a part of a better group of human beings, all the boys welcomed me with open arms and accepted me for who I was. This past year was by far the best group of guys I have ever been around in terms of how tightly knit the room was. There wasn’t anything that anybody wouldn’t do for one another both on and off the ice.

While I have never hidden the fact that I have autism, I have never wanted to be treated differently because of it. I have not let it keep me from working to achieve my dreams, and I hope that this article will show other people with autism that they can achieve their dreams, too. I may have autism, but it does not have me.