Derek Schaedig: Down But Not Out

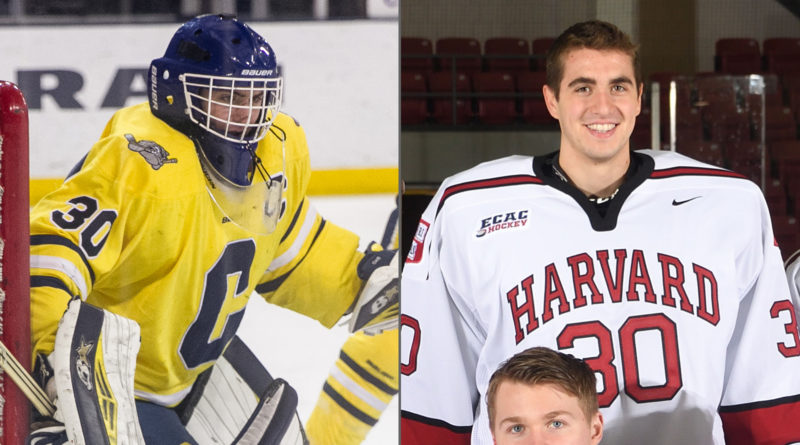

The following article was written by Chelsea native and Harvard goaltender Derek Schaedig for his university’s student newspaper, The Crimson. While in the process of writing his story, he contacted MiHockey and asked if it could be shared with his home state’s hockey community, as well.

My name is Derek Schaedig. I am a goalie for the men’s hockey team at Harvard; I am a sophomore studying Psychology; I am a writer for The Crimson; and in April 2019, I was diagnosed with major depressive disorder, more commonly referred to as depression. I am not immune to mental illness, and neither are many student-athletes.

It begins in my small town of Chelsea, Mich., in 2016. In the span of three years, my high school, with a student body of just under 900, endured the losses of three teenagers — one a student-athlete — to mental illness.

At the time, I didn’t want to understand this kind of pain. I was known amongst my high school peers as positive, hardworking, and happy. I couldn’t distinguish stress from anxiety, sadness from depression, or “being down” from disease. I believed my relentless optimism and mental fortitude could get me through anything. I believed I was immune to mental illness.

Just before I arrived at Harvard to begin my freshman hockey season, I learned that my new Crimson team would have to compete without one of its top forwards, Ty Pelton-Byce. Pelton-Byce was forced to take a year-long leave of absence from Harvard after his battle with depression left him unable to maintain his academic eligibility. Mental illness continued to recur in my life; I continued to believe that I was immune.

In 2013, Brian Hainline, chief medical officer of the National Collegiate Athletic Association, declared mental health to be the number one health and safety concern for student-athletes. Harvard, fielding 42 varsity teams, boasts the largest Division-I athletics program in the nation. Representing almost 17 percent of the undergraduate student body, 1,075 athletes suited up for the Crimson last year. And though mental health literacy continues to improve, for athletes at Harvard, a stigma remains.

My name is Derek Schaedig. I am a goalie for the men’s hockey team at Harvard; I am a sophomore studying Psychology; I am a writer for The Crimson; and in April 2019, I was diagnosed with major depressive disorder, more commonly referred to as depression. I am not immune to mental illness, and neither are many student-athletes.

The Hockey season comprises roughly seven of the nine months of the academic year. During the season, my morning begins at 7:30 a.m. I spend the middle portion of the day in the classroom. Then, with a few minutes set aside for lunch, at 1 p.m., I head to the rink for practice, followed by a 60-minute workout. I shower, receive treatment for physical injuries, and walk to the dining hall, where I eat dinner at around 6:45 p.m. I get back to my dorm and spend the rest of the evening catching up on homework, spending time with roommates, or getting to bed early in order to repeat the process the next day.

Though the rigors of a Division I schedule can vary from athlete to athlete, team to team, or even day to day, most student-athletes have a similarly busy daily routine.

I figured out how to manage these schedule logistics freshman year. Reconciling the academic requirements, however, was more difficult.

At freshman orientation, one of the many pamphlets I received asked: “Have you ever been in a competitive environment before?”

Of course I had. I had just finished two gap years playing an extremely competitive position in hockey against the best players my age. I had been traded between teams and cut from many others. I understood competition — or so I thought.

And yet, I was unprepared for a “competitive environment” as defined by Harvard. I studied for my first midterm rigorously. A week later, I received a 56 percent. For the following test, I was determined to redeem myself: I prepared even more diligently. This time, I received a 78 percent. I had never gotten below an B+ in my life. I was stunned.

I soon realized that everyone on campus was talented in one way or another, and that meant some students on campus were better than I was in different ways. While I spent a majority of my youth pursuing the sport I love, my new peers had been intensely preparing to excel in other arenas. This culture, combined with my demanding hockey schedule, left me — for the first time in my life — consistently failing.

Away from the classroom, I was competing to earn the position of starting goaltender for my team; however, my two upperclassmen goalie partners routinely outplayed me on the ice. I was now a third-string goaltender — another foreign position for me. I was expending immense amounts of energy and focus 12 hours a day in both the classroom and on the ice, and losing on both fronts.

Even now, this experience is difficult to articulate. At the time, with far less understanding of my symptoms, I simply felt terrified.

This feeling became a living, breathing nemesis. It consumed me; it replaced all emotions. It fought continuously to dampen my love for friends, family, school, and hockey.

I began to distance myself from both my teammates and my peers. I wanted to make new friends and experience everything college has to offer, but something in my mind seemed to relentlessly urge me not to. A battle was constantly being waged in my head — my outgoing, happy, positive self versus depression — and the former always lost.

My breaking point came with a few months remaining in the academic year. I skipped class for the third day in a row, unable to get out of bed, fighting an illness I wasn’t yet aware I had. I couldn’t stand it anymore. I was overwhelmed with fear. I felt hopeless. It seemed like there was no overcoming the monster in my mind.

For months, I had thrown every ounce of positivity I had in me at depression. I could escape it at times, but the disease was always waiting to pull me back into its grip. The only things that fended it off were isolation at times, playing guitar at others, and alcohol.

I drank with friends, at parties, and at dances — normal college kid stuff. But after all the laughter, lights, excitement, and people were gone, when no one was looking, I still drank, and no one knew. As I continued to spiral, I started to eat poorly. Then, I stopped eating altogether. At night, I wasn’t able to sleep, and sometimes, when the sun finally did rise, I could no longer work up the motivation to get out of bed.

The night I reached my breaking point, I left my dorm around 11 p.m., and I ran. I sprinted along the Charles River with no destination in particular. I just needed to be away. Around 1 a.m., I found myself hunched over on a bench, with tears streaming down my face and a brain plagued with suicidal thoughts.

After multiple attempts from my parents persuading me to reach out for help, I called Urgent Care, and began the process of finding the support I so desperately needed.

But one phone call isn’t an immediate solution. The process of recovery is long and difficult. Though my healing process had started, I continued to struggle.

One night toward the end of the hockey season, about a month after I first contacted Urgent Care, my head coach, Ted Donato, made a comment that might have saved my life. Following a game, he reminded us that we were short a great player and teammate in Pelton-Byce due to mental illness. He urged us to reach out for help if we needed it and to prioritize our mental health.

Prior to this conversation, mental health was simply not a topic of discussion on my team. My coach’s words gave me the comfort and courage I needed in order to bring my personal experience to his attention. His supportive response spurred a new stage in my healing process. I could finally acknowledge that I was not immune to depression.

Throughout the season, my seven fellow freshman hockey class members tried to lift my spirits. I knew they could tell I was down; I also knew they did not know why. At our end-of-year celebratory dinner, flanked by shouting waiters and sizzling entrees, I cautiously revealed my diagnosis to them. It was received with nothing but love and support, a reaction for which I am eternally grateful for and believe exemplifies my teammates’ outstanding character.

Since then, others on my team have come forward with similar experiences. One of my teammates described depression to me as an “invisible disease,” impossible to reckon with “until you’ve experienced it and realize just how real and daunting it truly is.”

Untreated mental illness is not a phenomenon limited to Men’s Hockey. I spoke to eight athletes from a range of Harvard teams who shared stories like mine.

“It can be hard to admit to yourself,” said a man on the soccer team. “It seems like something that happens to other people, but not you.” Others cited similar experiences struggling with depression, anxiety, body dysmorphia, and other mental illnesses.

These athletes agreed to speak on the condition of anonymity because of a stigma in athletics at Harvard that brands those who acknowledge their mental illness as weak. One Women’s Hockey player told me she “felt like I wasn’t allowed to feel this way, because on paper, my life was supposed to be perfect.”

There is still work necessary to improve access to mental health resources, reduce the stigma associated with mental illness, and boost overall awareness of the issue. Some of it is being done through new programs such as the NCAA’s Mental Health Task Force and Harvard’s Crimson Mind and Body Program, as both the NCAA and Harvard make drastic strides in their support for student-athletes’ mental health needs.

Depression, anxiety, various eating disorders, and other mental illnesses can affect anyone. They don’t care about social status, height, weight, gender, age, race, athletic ability, and academic accomplishments. They hide behind smiles and within our community. They are unnoticed in public, yet devastating in private. They are the ultimate equalizer.

If you are reading this and battling a mental illness, I want you to know that there is help for you, and it begins with talking to others about your disease.

I am currently taking a leave of absence from both school and hockey in order to continue to focus on my mental health. But through hard work, perseverance, and the services of Harvard’s Counseling and Mental Health Services, Oaklawn Hospital, McLean Hospital, and The University of Michigan, I will continue to battle my invisible disease, and I will return even stronger and healthier than before.

This is where my story ends, but my battle with mental illness forges on. The same goes for the other student-athletes in this story and the thousands of other students — athletes or not — across the nation who also struggle with mental illness. We have many more tests to take, goals to score, championships to win, and long, full, happy lives to live. We continue to battle our mental health disorders daily, but we are fighters, and we refuse to let our diseases stop us from chasing our dreams.

I would like to thank the many courageous student-athletes for commenting on this difficult subject matter as well as The Crimson, my family, friends, teammates, coaches, the Harvard athletic training staff, Advantage Strength and Conditioning, the mental health services at CAMHS, The University of Michigan, McLean and Oaklawn Hospital for helping me get to a place in my battle with mental health to be able to write this article.

If you or someone you know needs someone to talk to, please contact the National Suicide Prevention Hotline at 1-800-273-8255. You are not alone.